There it hit me. Had my 23-year-old son been born in Ramallah he would either be in prison now, or dead.

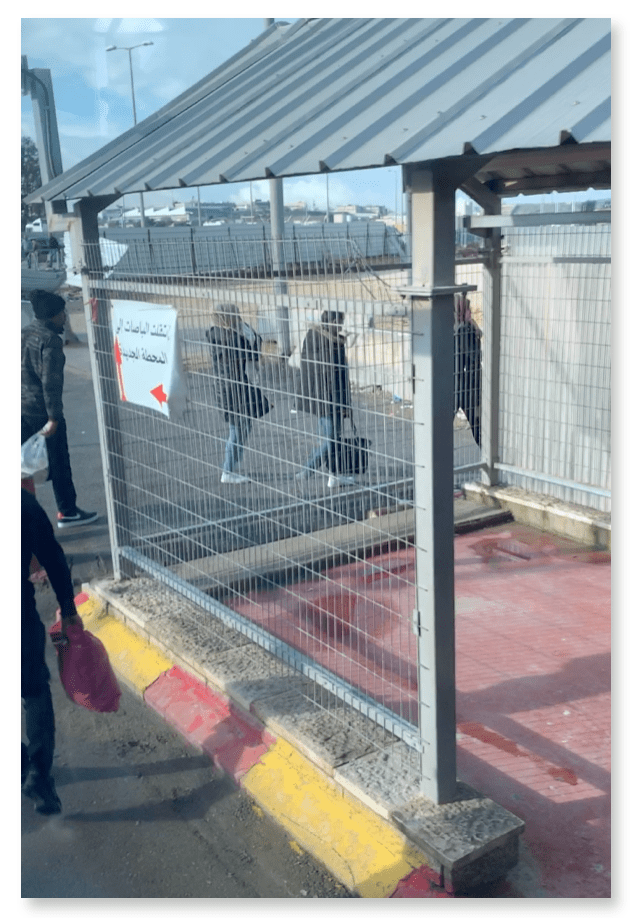

“There” was standing inside a chain link holding pen while waiting to be processed through the security checkpoint called Qalandiya. Qalandiya is the notorious crossing point between Ramallah and Jerusalem, a cut in the Separation Barrier that thousands of Palestinians funnel through each day, travel permits in hand to go to work, shop, see friends or family, visit the Al-Aqsa Mosque or even the hospital in Jerusalem.

In other words, to live.

Ramallah is the de facto capital of Palestine in the West Bank, an “Area A” city which means the Palestinian Authority has full control — civil and security — of the town. It is the seat of the Palestinian Authority governing body — Mohamoud Abbas has his office there — and home to the Yasser Arafat Museum. Which makes Ramallah about as Palestinian as you can get.

This place oozes “Free Palestine,” which is why I chose to live there for two weeks during my two-month trip to the Holy Land. I made a point of living in different neighborhoods, both Jewish and Arab, to get a better sense of their respective day-to-day lives. Ramallah was the most uber-Palestinian neighborhood I could find within commuting distance to Jerusalem where I worked.

This place oozes “Free Palestine,” which is why I chose to live there for two weeks during my two-month trip to the Holy Land. I made a point of living in different neighborhoods, both Jewish and Arab, to get a better sense of their respective day-to-day lives. Ramallah was the most uber-Palestinian neighborhood I could find within commuting distance to Jerusalem where I worked.

But more importantly to me, to get from Ramallah to Jerusalem I had to cross through the Qalandiya checkpoint each day. For some reason, I wanted to experience that for myself.

A TWO-HOUR TIME SUCK

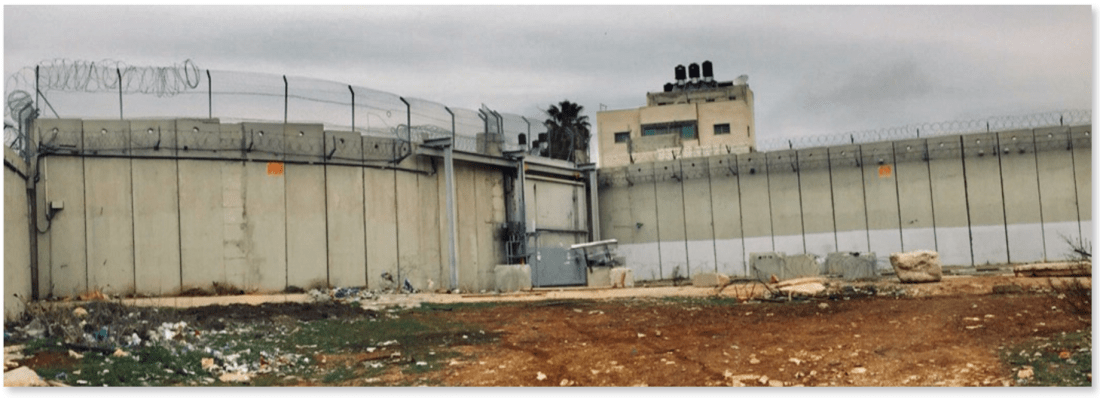

The Separation Barrier here was built by Israel in 2002 during the Second Intifada, ostensibly as a security measure. (The Separation Barrier was declared illegal in 2004 by the International Court of Justice, by the way…just sayin’.)

Qalandiya is more of a chokepoint than a checkpoint when it comes to traveling the twelve miles between the two cities, making what normally should be a 15-minute commute into Jerusalem oftentimes a two-hour trek.

Qalandiya is more of a chokepoint than a checkpoint when it comes to traveling the twelve miles between the two cities, making what normally should be a 15-minute commute into Jerusalem oftentimes a two-hour trek.

I met a young Palestinian from Ramallah working at the coffee shop just inside the Jaffa Gate in the Old City next to the Christian Information Centre, the epicenter of tourism. He told me he had to leave his house by 5:00am to make sure he got to work by 7:00am. If he were late for work he might lose his tough-to-come-by job. It takes him another two hours to get home. Between customers, I watched him FaceTime his daughter to wish her well at school that day. He showed me pictures of his beautiful wife and daughters, which made we wonder how different his life would be — how any of our lives would be — if given an extra four hours of free time to spend with family.

My commute took just a little over an hour because I left later in the morning to avoid rush hour. Each morning around 8:30am I would go to the main bus terminal in the center of Ramallah to grab the #218 to Jerusalem. “Terminal” is a bit of a stretch. It is more like a dirt parking lot where big busses and short shuttles jostle for space, working their way in and out of the parking lot like a ballet of elephants. Somehow it works.

I’m still not sure if my bus had a formal departure time. It seemed to me that the bus driver would take off once the bus was sort of full and he had finished his cigarette and was done chatting with the other drivers hanging out in front of their busses, smoking cigarettes and drinking Turkish coffee. Or in the case of some drivers, finish their morning prayers.

I’m still not sure if my bus had a formal departure time. It seemed to me that the bus driver would take off once the bus was sort of full and he had finished his cigarette and was done chatting with the other drivers hanging out in front of their busses, smoking cigarettes and drinking Turkish coffee. Or in the case of some drivers, finish their morning prayers.

Turkish coffee in hand, I’d get on the bus and take a window seat. The bus would slowly but surely fill up, the ticket-seller walking down the aisle collecting the 7 shekels ($2) it cost for a one-way trip into East Jerusalem near Damascus Gate. Everyone on the bus was Palestinian except me. Most of the women were covered, some held little children.

Turkish coffee in hand, I’d get on the bus and take a window seat. The bus would slowly but surely fill up, the ticket-seller walking down the aisle collecting the 7 shekels ($2) it cost for a one-way trip into East Jerusalem near Damascus Gate. Everyone on the bus was Palestinian except me. Most of the women were covered, some held little children.

Once properly filled, the #218 elephant would gracefully back out of the parking lot onto the main street, then work its way through the city. It rolled heavy down the curvy three-mile hill towards the checkpoint. The further down the hill we went, the grittier the neighborhoods became. Clothing stores, shawarma stands and what seemed to be an inordinate number of auto repair shops lined the trash-strewn boulevard. The Amari Refugee Camp, home to 2,000 Palestinian refugee families, was down the hill on the right hand side, its entry marked by an archway under which few seemed to travel in or out.

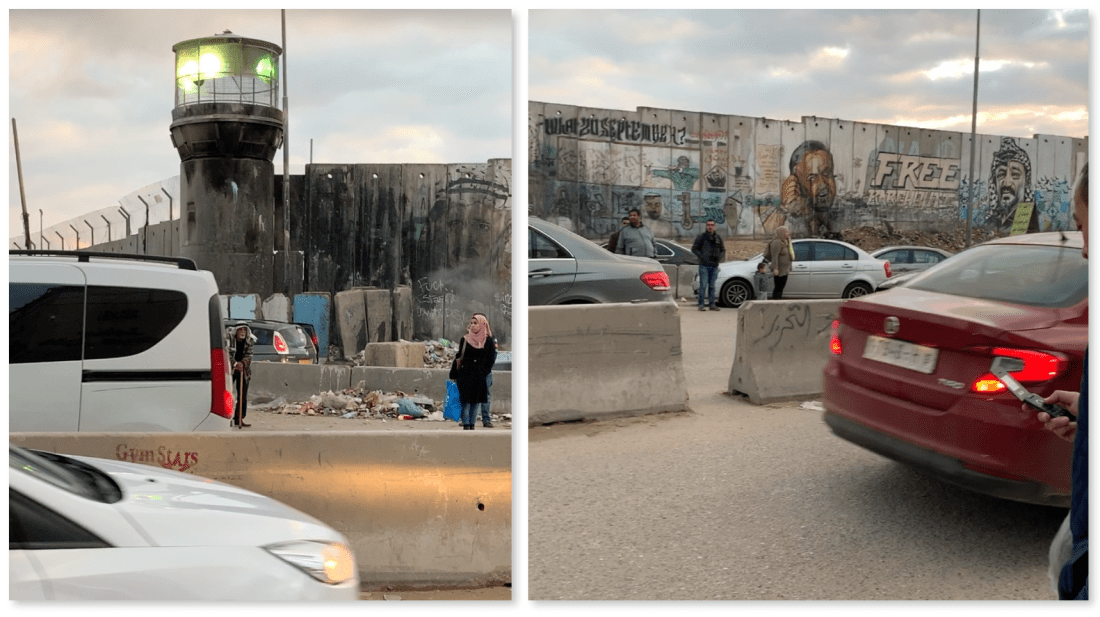

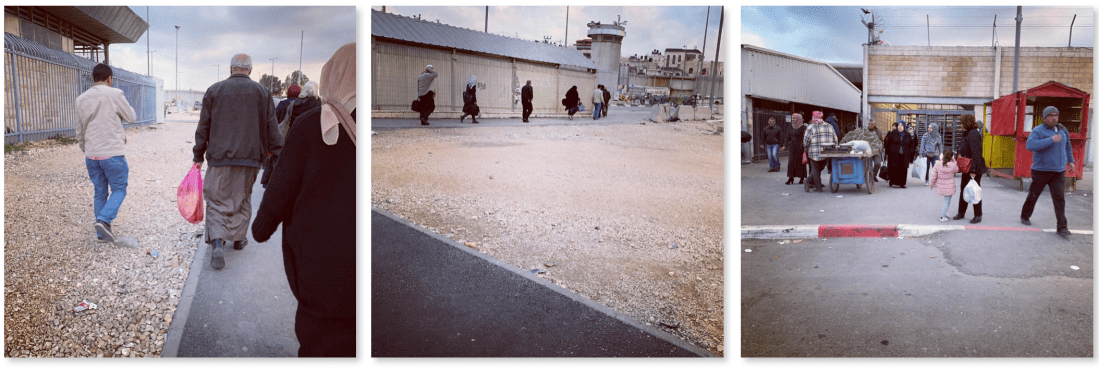

At the bottom of the hill, busses, cars, taxis and shuttle vans clogged the intersection that lead to the checkpoint. People darted in and out of traffic as they worked their way to and from the foreboding barrier topped with barbwire and delicate accents of chainlink fence. Armed security guards looked down from watch towers, seemingly not yet having had their morning coffee to perk up their spirits, as had I, thankfully.

At the bottom of the hill, busses, cars, taxis and shuttle vans clogged the intersection that lead to the checkpoint. People darted in and out of traffic as they worked their way to and from the foreboding barrier topped with barbwire and delicate accents of chainlink fence. Armed security guards looked down from watch towers, seemingly not yet having had their morning coffee to perk up their spirits, as had I, thankfully.

All of this from the window of my big Arab bus.

CLUCK-CLUCK

CLUCK-CLUCK

While checkpoints are a time suck, what’s worse is, they are demeaning. Whether you are driving through on the city bus or walking through on foot, the whole experience makes you feel like a criminal.

For the entire time I lived in Ramallah, I took the city bus into Jerusalem. And every day when the bus got to the checkpoint and most Palestinians were required to get off and pass through security on foot, I stayed safely in my seat under the protection of my international passport. “Cluck-cluck” I thought to myself. You’re a chicken.

I don’t know if it was lack of courage on my part or a surplus of wisdom, but each morning I chose not to tempt fate.

Here is how the checkpoint works:

The city bus pulls up nose-to-nose to the barrier gate and stops, gate shut tight. On the other side are a handful of Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers standing there, chatting with each other, cell phones in hand, machine guns over their shoulders. Just another day at the office for them, it seems. No hurry to pass us through.

Once the bus stops at the gate, most everyone gets off and proceeds on foot through the turnstile to the right of the gate, kids and all. Palestinians need special permits to get into and out of Jerusalem, hence the term “check” point. I am able to stay on because of my international passport, as are a few others who must have special travel documents.

Two IDF soldiers approach the bus to check our papers. The first soldier sticks his head through the front door and quickly scans those still on, profiling for trouble. I find myself looking at my feet, feeling guilty of what, staying seated? He then comes fully on board, machine gun at the ready. Once the coast is clear he steps aside to let a second IDF soldier on — each day a young woman about my daughter’s age — her machine gun slung over her shoulder so that her hands are free to grab ID’s and punch in numbers on her iPad. And, of course, shoot if necessary. Soldier One follows behind, eyes on the riders.

Two IDF soldiers approach the bus to check our papers. The first soldier sticks his head through the front door and quickly scans those still on, profiling for trouble. I find myself looking at my feet, feeling guilty of what, staying seated? He then comes fully on board, machine gun at the ready. Once the coast is clear he steps aside to let a second IDF soldier on — each day a young woman about my daughter’s age — her machine gun slung over her shoulder so that her hands are free to grab ID’s and punch in numbers on her iPad. And, of course, shoot if necessary. Soldier One follows behind, eyes on the riders.

Needless to say, I have no pictures of this event. It just didn’t seem like a wise move on my part to pull something out of my pocket and point it at an armed IDF soldier at that moment in time.

Once the soldiers check everyone, they exit out the back door of the bus. Eventually (maybe 5 minutes later, maybe 20 depending on the mood of the guards inside the compound) the gate opens and the bus moves ahead a bus-length until it reaches another gate. The gate behind us slams shut, pinning us in like a bull ready to be let loose on a bull ride (sans cowboy). At that point, everyone gets off the bus. We walk through the forward gate where we meet up with the people who were required to get off the bus at the first gate to walk through special security.

All of us are now in Jerusalem. Together we hoof it, bags and babies in hand, 50 meters to catch another bus into the city.

That’s how it works 365 days a year.

I did this day after day for two weeks, never building up the nerve to get off the bus to walk through the first turnstile with the others. I was afraid to mess with the IDF soldiers, to tempt fate. Once they saw my passport and realized I was walking through unnecessarily, would they hold me for hours of questioning? Would they confiscate my phone and computer? I didn’t want to risk it, so I stayed on the bus. Cluck-cluck.

SUCK IT UP

After two weeks in Ramallah, I moved back to East Jerusalem. But the thought of my never having walked through Qalandiya gnawed at me. So the next week I hitched a ride into Ramallah with my Palestinian friend, Zaina, who was going there for a job interview. Zaina, with her yellow license plate, cruised through the checkpoint with barely a tap of her brake (it is easy to LEAVE Jerusalem to enter Ramallah. It’s ENTERING that causes a bit of angst!) I left my computer and mobile phone at the hotel.

We drove no more than 100 yards before I said, “This is good.” She looked at me like I was crazy, hit the brakes and stopped. We were in a mash-up of traffic, people, coffee stands, street vendors…and guard towers.

“Here?” she asked. “HERE?” Cars zipped past.

Yep. I said thanks and jumped out. Zaina shrugged and drove off as if she had done this a thousand times before.

Just in case someone was watching me from the security tower (paranoia is rampant and warranted), I crossed the street and killed time walking around the coffee carts and fruit stands that are sprinkled around the main intersection.

I drained two shots of thick, black coffee and a slammed down a banana before walking toward the checkpoint, doing my best to meld in with the locals. Like, right.

Up the sidewalk I went, passing the row of busses lined up like elephants at the gate and through the first turnstile. I emptied out into what can’t be described as anything other than a holding pen, fenced in to the left, right and above, nowhere to go but forward.

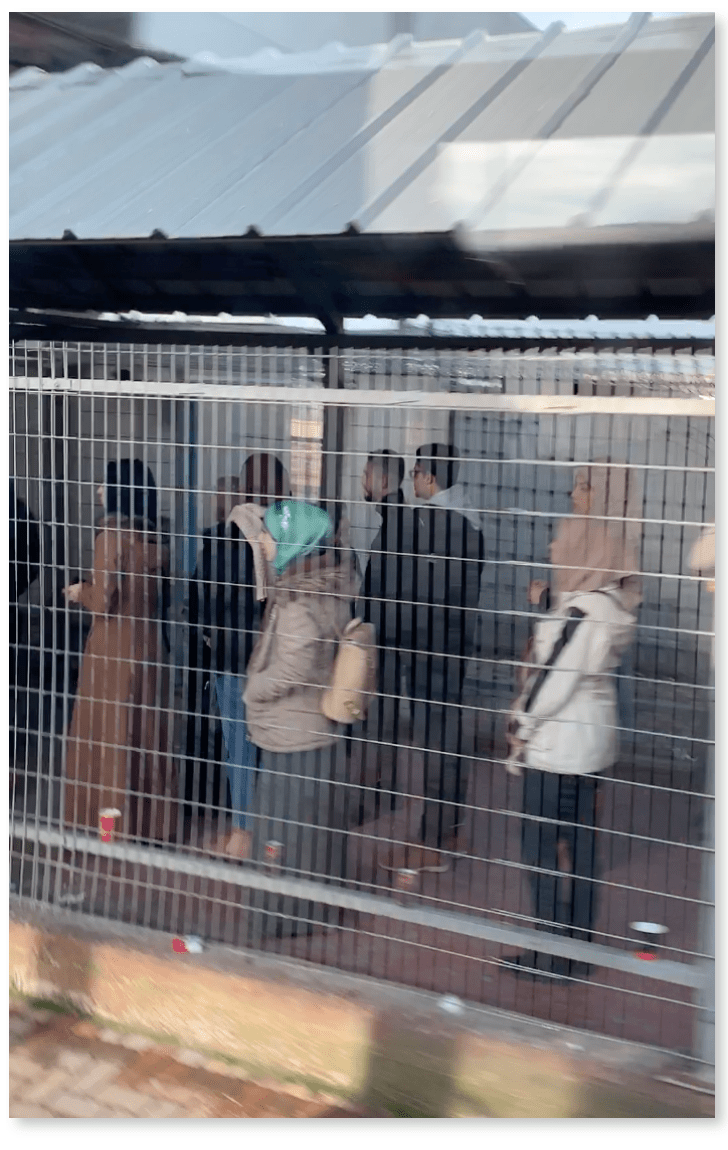

There I waited with dozens of other Palestinian commuters to go through a second turnstile that would take us into a security area much like an airport security check with metal detector, conveyor belt, x-ray machine and cameras. And guards. Plenty of guards.

While waiting in the pen I was just feet away from three young IDF soldiers, younger than my son, on the outside of the fence. They were hanging around talking, checking their phones for messages from their girlfriends (I assume) — totally indifferent to people on my side of the fence who were anxious to get to work for fear of losing their jobs.

While waiting in the pen I was just feet away from three young IDF soldiers, younger than my son, on the outside of the fence. They were hanging around talking, checking their phones for messages from their girlfriends (I assume) — totally indifferent to people on my side of the fence who were anxious to get to work for fear of losing their jobs.

When I started getting frustrated with the wait-time and maddening indifference of the 20-year-old IDF soldiers — that is when it hit me that if my son lived in Ramallah he would be dead or in prison. Here I was, a middle-aged man with no place to be, no deadline to hit, no family to provide for, getting pissed off that I was waiting in a cage to be processed through to Jerusalem by these young IDF soldiers who couldn’t care less.

If I felt this way, my son wouldn’t stand a chance! He almost got in a fight with three young Spaniards at a Burger King in Pamplona because he thought they were talking about him while he was in line to buy a Whopper. (They were speaking in Spanish, mind you, and he doesn’t understand Spanish). They just looked at him funny, he told me later, and were laughing.

I couldn’t imagine for one second that my son would keep his mouth shut to these IDF guys and be dutifully, passively, processed through this checkpoint like cattle on their way to market. Once, maybe twice. But day in and day out, as part of his daily routine to and from work — subjected to this treatment four hours EACH DAY??? Absolutely no way. Where’s a rock?

To be honest, I found the young Palestinian men and women to be incredibly disciplined and honorable in how they handled this situation. I know for a fact they were not giving up on their fight for justice, nor passively acquiescing to the challenge of living under occupation. They just seemed to know when and how to choose their battles. And they needed to get to work. They were strong. They were disciplined.

Finally, it was my turn through the second turnstile. Shoes off, belts off, everything out of my pockets, bags through the scanner, through the metal detector I went. On the other side of the scanner I walked up to a bullet-proof glass window and held up my passport and travel visa for the guard to check. She was leaning back in her chair, feet up on the table. She looked up from her phone to glance at my passport and then nodded me through. No WAY could she have read the small print on the visa from that distance. She just knew I wasn’t Arab.

I grabbed my stuff off the conveyor belt, put my shoes back on and walked with the others to catch the #275 bus into Jerusalem.

As I looked out the window as the bus drove away, all I could think was, “Wow, that really sucked.” And then I imagined what it would be like if I were on my way to visit my son in prison, or worse.

As I looked out the window as the bus drove away, all I could think was, “Wow, that really sucked.” And then I imagined what it would be like if I were on my way to visit my son in prison, or worse.

Now THAT would suck.

PalRael

Dr. Omer Salem

Dr. Omer Salem Attendee ‘Navad” (l) and Dr. Yehuda Stolov

Attendee ‘Navad” (l) and Dr. Yehuda Stolov Dr. Stolov (l) and Dr. Salem (r)

Dr. Stolov (l) and Dr. Salem (r) Created by the Jerusalem Arts Network, Shafaq, in 2017, Jerusalem Nights offered 20 distinct live events over the four-day period ranging from a Christmas Tree lighting and carols with the Palestine Brass Band, to art exhibits, dance workshops, concerts, educational symposiums and more.

Created by the Jerusalem Arts Network, Shafaq, in 2017, Jerusalem Nights offered 20 distinct live events over the four-day period ranging from a Christmas Tree lighting and carols with the Palestine Brass Band, to art exhibits, dance workshops, concerts, educational symposiums and more.

One of the subtle creative expressions I noticed was how, on the promotional poster for Jerusalem Nights, they overlapped a representation of the Palestinian flag with the EU flag as a work-around to the Israeli ban on using the Palestinian flag.

One of the subtle creative expressions I noticed was how, on the promotional poster for Jerusalem Nights, they overlapped a representation of the Palestinian flag with the EU flag as a work-around to the Israeli ban on using the Palestinian flag.